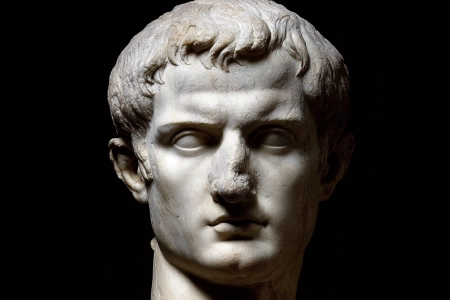

Caligula: A Biography of Rome's Most Notorious Ruler

Explore Caligula's rise, rule, and assassination.

Reading time: ~7-8 min

Introduction

Born Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus at Antium in 12 CE, the third Roman emperor is remembered by his childhood nickname Caligula (“little boots”), earned while accompanying his father Germanicus among the Rhine legions. His short reign, 37-41 CE, became a byword for the “mad emperor.” This biography looks past legend to ask who was Caligula, what he actually did, and why he was assassinated. We follow his early life, accession after Tiberius, fraught relations with the Senate and Praetorian Guard, domestic policies, and the palace plot that killed him, while sorting myth vs. history on horses, seashells, and floating bridges.

Family, Childhood, and the Making of “Caligula”

Germanicus, adopted by Tiberius and beloved by the army, and Agrippina the Elder, Augustus's granddaughter, gave Gaius impeccable pedigree within the Julio-Claudian dynasty. As a charming child in miniature gear, he toured frontier camps and earned the nickname Caligula from soldiers' caligae (hobnailed boots). After Germanicus's death (19 CE) and Agrippina's exile, the family suffered purges, teaching the young prince the arts of silence and survival at court. Brought later to Capri, he observed Tiberius's suspicious court politics at close range.

Accession and the Golden Months (37 CE)

When Tiberius died in 37 CE, his will named Gaius co-heir with Tiberius Gemellus. With decisive help from the Praetorian Prefect Macro, the Senate acclaimed Caligula as emperor. Early measures won acclaim: remitting unpopular taxes, granting bonuses to the Praetorians and urban populace, recalling exiles, and staging lavish games. Rome embraced the youthful princeps after years of Tiberian secrecy. That same year, however, a serious illness struck. Ancient authors frame a post-illness “change,” but modern historians note that as Caligula asserted power, senatorial hostility sharpened.

Caligula and the Senate: Performance, Power, and Payback

Caligula pressed an increasingly monarchical style. He demanded deference, revived or manipulated maiestas (treason) trials, and performed authority through spectacle and public humiliations. Senators recorded this as tyranny; for the emperor, it advertised who ruled. Meanwhile the Praetorian Guard—kingmakers then and later—enjoyed favor, pay, and proximity. The triangle of emperor, Senate, and Guard generated the tensions that fill ancient narratives.

Policies at Home: Taxes, Games, and Administration

Taxes & Finance

Early tax remissions and lavish spectacles pleased crowds but strained revenue. Later stories of financial crisis blend reality (high spending, extraordinary levies, auctions, and confiscations) with hostile exaggeration. Caligula also pressed provincial extractions—typical of emperors balancing army and urban costs.

Games & Public Works

The regime invested in gladiatorial shows and chariot races, reinforcing the image of princeps as provider. Construction and embellishment on the Palatine Hill and spectacular temporary works—especially at Baiae—fed both popularity and later legends.

Administration & Elites

Caligula raised capable equestrians to key roles and managed client kings. To senators, the promotion of non-senatorial elites read as insult; to an emperor, it was practical governance and faction-balancing.

Religion and the Imperial Cult

Caligula emphasized the sacral aura of emperorship, experimenting with divine iconography and accepting ruler cult honors where Greek practice allowed. In Judea, reports by Philo of Alexandria speak of a crisis over placing the emperor's statue in the Jerusalem Temple—averted before completion. Whether read as megalomania or policy, the message was clear: loyalty to Rome had a religious dimension.

Abroad: Britain, Germany, and the “Seashells”

Caligula assembled forces near the Channel and staged coastal maneuvers that ancient authors mocked. The famous anecdote of collecting seashells as “spoils of the ocean” (and the pontoon bridge at Baiae) reads as farce to later writers. Modern views see logistical reconnaissance, morale theater, and symbolic claims over the sea when a Britain invasion was postponed.

Court, Family, and Scandal

Caligula's marriages and relationships—especially the closeness to his sisters, notably Drusilla—fueled scandalous storytelling in Suetonius. Behind gossip lay politics: imperial households brokered alliances; sudden shifts in favor created enemies; and the emperor's public intimacy—banquets, entrances, staged appearances—was itself a language of rule.

The Assassination: Who Killed Caligula—and Why?

On 24 January 41 CE, a palace conspiracy led by Cassius Chaerea of the Praetorian Guard attacked Caligula after a performance, killing him and, amid chaos, his wife Caesonia and their infant daughter. Motives mixed personal grievance, fear provoked by humiliations and trials, and senatorial resentment. While the Senate mused about restoring the Republic, rank-and-file Praetorians found Claudius in the palace and proclaimed him emperor, confirming the Guard's role in succession.

Myth vs. History: Sorting the Stories

Was Caligula “Insane”?

Ancient authors deploy madness to moralize about absolute power and to justify assassination. Modern readings see performance politics pushed beyond senatorial taste, plus genuine erratic episodes—not proof of total derangement.

Did Caligula Make His Horse Consul?

No reliable evidence that Incitatus held office. The tale likely satirizes Caligula's contempt for the Senate, implying he could elevate anyone—even a horse—above them.

The “Seashells” Campaign

Suetonius and Cassius Dio describe soldiers collecting shells as “spoils of the ocean.” Read as ritualized theater and propaganda during a postponed crossing, not literal conquest.

The Bridge at Baiae

A pontoon bridge over the Bay of Baiae, ceremonially crossed by the emperor, signaled wealth and control. Technically feasible, it showcased imperial command more than delusion.

How Reliable Are the Sources?

We rely on Suetonius, Cassius Dio, and Philo of Alexandria, each writing with agendas, at distance, or from elite perspectives. Critical reading and corroboration are essential.

Caligula's Rome: Daily Life Under the Princeps

For the urban plebs, the reign meant frequent spectacles and a visible emperor. For senators, it meant anxiety about status and safety. For the Praetorians, it meant pay and proximity to power—until the blades turned inward. In the provinces, governors balanced taxation, justice, and the emperor's sacral messaging.

Caligula and the Julio-Claudian System

The Julio-Claudian Principate rested on adoption, dynastic prestige, and army loyalty rather than hard law. The Senate kept honor without decisive power; the Praetorian Guard gained leverage as maker and unmaker of emperors. Caligula pressed a more sacral monarchy than Augustus had veiled. The elite recoil—and his death—reveal the system's limits.

Timeline: Life, Reign, and Legacy

- — Birth at Antium of Gaius (Caligula).

- — Death of Germanicus; family conflict with Tiberius.

- — Gaius to Capri; learns court politics.

- — Caligula becomes emperor; early popularity; serious illness.

- — Tense Senate relations; spectacles; religious controversies.

- — Northern displays; Baiae bridge; “seashells” anecdote.

- — Assassination by Cassius Chaerea; Claudius succeeds.

Conclusion: Caligula's Place in Roman History

Strip away sensationalism and Caligula remains a revealing figure of the Julio-Claudian order: a princeps who turned theater into policy, punished elites, and sacralized his rule. His fall—engineered by Praetorians and tolerated by senators—underscores Rome's governing logic: keep the soldiers, feed the crowds, and manage the aristocracy. Fail, and even an emperor can die in a corridor.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why was Caligula assassinated?

A mix of elite hostility, Praetorian grievances, and fear generated by humiliations and treason trials. Cassius Chaerea led the palace plot.

What did Caligula really do as emperor?

Early tax remissions, heavy spending on games, centralization of authority, assertive religious messaging, and punitive measures against rivals—often theatrical.

Was Incitatus made consul?

No. The horse story is satire about the Senate's dignity, not a literal appointment.

How reliable are sources on Caligula?

We depend on Suetonius, Cassius Dio, and Philo, all with bias and distance; cross-reading and context are crucial.

What happened after Caligula's death?

The Senate hesitated; the Praetorians proclaimed Claudius, and the Principate continued with adjustments.

Sources & References

- Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars (Caligula).

- Cassius Dio, Roman History (Books 59-60).

- Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius.

- Anthony A. Barrett, Caligula: The Corruption of Power.

- Aloys Winterling, Caligula: A Biography.

- Mary Beard, SPQR (context for the early Principate).