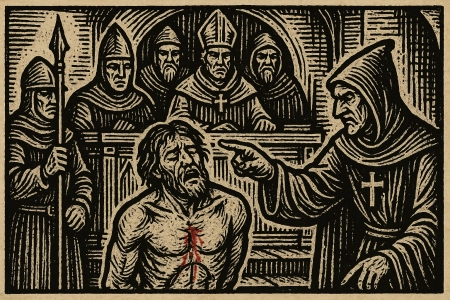

The Inquisition: Heresy Trials and Torture

How church courts investigated heresy — and how fear, law, and confession shaped life for centuries.

Introduction

For centuries, the word Inquisition has evoked images of secret tribunals, heresy trials, and the ominous threat of inquisition torture. Yet inquisition history is more than lurid tales. It is also a story of church authority and control, evolving legal culture, and the politics of medieval justice and religion. This article offers the inquisition explained—from its origins in the medieval inquisition of the 13th century to the rise of the Spanish Inquisition, the Roman Inquisition, and the institution's decline in the 19th century. Along the way, it separates myth from documentation, draws on inquisition archives and confessions, and asks what the Inquisition's legacy in the modern world really is.

What Was an “Inquisition”? The Tribunal of Faith

In medieval Latin, inquisitio meant a formal inquiry. Church courts and secular rulers alike used inquisitorial procedures to investigate serious crimes. When applied to heresy, a specialized system emerged—often called a tribunal of faith—to defend religious orthodoxy enforcement.

- Public summons and grace period: Suspects were called to confess and denounce heresy voluntarily—often with lighter catholic heresy punishment if they complied.

- Learned judges: Clerics trained in canon law led the process; lay officials assisted with arrest, custody, and penalties.

- Confession-centered: Inquisitors and confession were inseparable: confession functioned as evidence and as a spiritual remedy.

- Church-state cooperation: Convicted, obstinate heretics were handed to secular authorities for corporal penalties.

Crucially, there was not one Inquisition but multiple inquisitions across regions and centuries—related, but never identical.

At a Glance: The Major Inquisitions

| Institution | Approx. start | Who controlled it | Typical targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medieval (Papal) Inquisition | 1230s | Papal authority; local church courts; city cooperation | Cathars, Waldensians, local heresy movements |

| Spanish Inquisition | 1478 | Spanish Crown (with papal authorization) | Conversos, Moriscos, Protestants (limited), blasphemy, policing orthodoxy |

| Roman Inquisition (Holy Office) | 1542 | Papacy; centralized curial tribunal | Reformation-era doctrine, censorship, high-profile cases (e.g., Galileo) |

For a parallel on how institutions can turn punishment into public spectacle, see The Roman Colosseum.

Origins of the Inquisition (13th Century)

Cathars, Waldensians, and Papal Response

In the 1100s-1200s, Southern France and Northern Italy saw reform movements like the Cathars and Waldensians. After failed preaching campaigns and periodic wars, popes developed a more systematic legal response. In the 1230s, papal initiatives empowered trained friars—especially Dominicans—to pursue heresy using standardized procedures: the medieval inquisition was born.

Papal Bulls and Legal Framework

The legal basis hardened through papal legislation, canon law, and cooperation with secular rulers. In 1252, Pope Innocent IV’s bull Ad extirpanda allowed civic authorities to use torture in heresy cases under stated limits—notably, without causing death or permanent injury. In theory, it was meant as a regulated tool of interrogation rather than a default step, and inquisitors still relied heavily on testimony, reputation, and written depositions. In practice, however, the boundary between “regulated” and “coercive” could be thin, especially when fear, politics, or local pressure demanded quick confessions.

Confession sat at the center of inquisitorial procedure — treated as both evidence and a path to repentance.

The Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834): Crown, Conversion, and Control

Foundation and Purpose

Authorized in 1478 CE, the Spanish Inquisition answered to the Spanish Crown (Ferdinand II and Isabella I) as much as to Rome. Its first mission targeted conversos—Jews and later Muslims who had converted to Christianity—amid suspicion of false conversion. Over time it pursued Protestants, alumbrados (mystics), bigamists, blasphemers, and, intermittently, witchcraft.

Torquemada and the Spanish Crown

Tomás de Torquemada, appointed Inquisitor General in 1483 CE, became a symbol of rigor. Under him, the Inquisition refined bureaucracy: standardized manuals, prison oversight, and records that fill vast inquisition archives and confessions today. The synergy of Torquemada and the Spanish Crown reveals how doctrinal policing fused with dynastic policy and church authority and control.

Procedure and the Auto-da-fé

The auto-da-fé ceremonies—“acts of faith”—publicly displayed penance and verdicts, sometimes followed by secular executions. The spectacle dramatized religious orthodoxy enforcement, projecting unity of crown and church to townspeople and foreign observers alike.

Facts About the Spanish Inquisition: Numbers and Myths

- Executions: Modern estimates are far lower than older polemical claims — still brutal, but not the near-mythic figures often repeated.

- Torture: Documented usage varies by tribunal and period; some studies suggest it was applied in a minority of cases, though its threat had wide impact.

- Records: The Inquisition produced unusually detailed paperwork, which historians now use to reconstruct everyday life, belief, and social conflict.

For a cultural parallel on public spectacle and punishment, see The Roman Colosseum.

The Roman Inquisition (1542-19th Century): Orthodoxy in the Age of Print

In 1542 CE, Pope Paul III established the Roman Inquisition as part of the Catholic Reformation's response to Protestantism and other doctrinal threats. Unlike Spain's crown-driven model, the Roman office tied closely to papal governance and Italian dioceses.

Galileo's Trial and the Limits of Science

The best-known case is Galileo Galilei (condemnation in 1633 CE). The trial's symbolism—science vs. doctrine—often overshadows its legal complexity, but it reveals the Inquisition's stake in policing ideas during a century reshaped by the printing press. For the broader revolution in information, see The Printing Press.

Inside the Process: Heresy Trials, Evidence, and Penalties

How a Case Began

A denunciation or rumor could trigger a summons. Some jurisdictions offered grace periods for voluntary confession with lighter penance. Depositions gathered testimony—often from neighbors or associates—creating the documentary backbone historians study today.

Evidence and Confession

Inquisitorial justice sought moral certainty rather than a modern “beyond reasonable doubt.” Confession remained central, with judges probing for doctrine and repentance.

What Method Did the Inquisition Sometimes Use to Force Confessions?

The most common “pressure” was not a device — it was the system itself: secrecy, detention, repeated questioning, and the threat of escalation. Torture existed within inquisitorial law, but it was generally framed as a last-step tool used when officials believed heresy was strongly indicated yet not fully proven.

- Psychological pressure: isolation, uncertainty, fear of witnesses, and prolonged custody.

- Threat of torture: in some cases, the threat alone pushed suspects to confess.

- Strappado (garrucha/cuerda): suspension by bound wrists, sometimes with weights.

- Rack (potro): gradual stretching of limbs.

- Water torture (toca): cloth and forced water ingestion to simulate drowning.

Importantly, frequency varied by region and era. Some research suggests torture was used in a minority of cases in many tribunals, even while it remained a terrifying possibility that shaped behavior and testimony.

Torture required legal thresholds, was to be recorded, and by rule could not draw blood or threaten life—restrictions that shaped practice but did not remove cruelty. Many trials ended without torture; in some, threat sufficed.

Sentences and Penance

Outcomes ranged from prayers, pilgrimages, fines, and property penalties to imprisonment and, for the obstinate, delivery to secular justice. The auto-da-fé dramatized closures; not every trial ended in death, but the possibility overshadowed all.

Faith, Fear, and Society: Why the Inquisition Endured

The Inquisition aligned with fear and faith in medieval Europe, rulers' desire for unity, and a growing bureaucratic logic of registers and manuals. Power varied by region, but everywhere the possibility of investigation pressured behavior, speech, and reading—shaping the history of religious persecution.

For lives upended by doctrinal conflict, compare Joan of Arc and the darker legends around Elizabeth Báthory.

Legend vs. Evidence: Myths, Numbers, and the Black Legend

Nineteenth-century polemics and popular culture magnified the Inquisition's worst features into an all-consuming horror, especially in the anti-Spanish “Black Legend.” Modern scholarship, using inquisition archives and confessions, corrects exaggerations—finding fewer executions than once claimed, more routine penance, and a legalism that—while chilling—was not pure chaos. Yet nuance should not dull moral clarity: coercion violated conscience, repressed dissent, and chilled inquiry for generations.

The End of the Inquisition (18th-19th Centuries)

From the 1700s onward, Enlightenment critiques of medieval justice and religion, secularization, and Napoleonic reforms weakened inquisitorial courts. The Portuguese Inquisition ended in 1821 CE; the Spanish Inquisition in 1834 CE. The Roman office evolved into other doctrinal bodies in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The legacy of the Inquisition in modern times is paradoxical: its records helped historians reconstruct the past, while its reputation helped modern Europe define ideals of conscience, toleration, and due process.

The Inquisition Explained—A Short Summary

The Inquisition was not one tribunal but many, emerging in the 13th century to protect Catholic orthodoxy. It evolved into powerful institutions—especially in Spain and Rome—that conducted heresy trials, used regulated inquisition torture, staged auto-da-fé, and intertwined with royal and papal politics. While modern research corrects exaggerated numbers, the system's coercion left a lasting mark on European society, law, and memory.

Conclusion: Memory, Morality, and Caution

In a Europe riven by religious passion and political rivalry, the Inquisition made faith a matter for courts. Its bureaucratic sophistication and theatrical punishments secured religious orthodoxy enforcement—and a culture of fear. Today, as societies debate security, speech, and belief, inquisition history cautions against systems that claim moral certainty while curtailing conscience.

FAQ

What method did the Inquisition sometimes use to force confessions?

The most common pressure was procedural — detention, secrecy, repeated questioning, and the threat of escalation. In some cases, tribunals used torture (such as strappado, the rack, or water torture) under legal rules that varied by region and period.

Who was put on trial during the Inquisition?

Targets depended on the place and century. Medieval tribunals focused on heresy movements (such as Cathars and Waldensians). The Spanish Inquisition often pursued suspected false converts (conversos and later Moriscos), plus offenses like blasphemy, bigamy, and banned ideas. The Roman Inquisition focused on doctrine and censorship during the Reformation era.

How did the Inquisition punish those found guilty of heresy?

Many sentences were non-lethal: prayers, pilgrimages, fines, wearing a penitential garment, or imprisonment. Persistent or “obstinate” heresy could lead to being handed to secular authorities for corporal punishment, including execution in some cases.

What was an auto-da-fé?

An auto-da-fé (act of faith) was a public ceremony where verdicts and penances were announced. It could include reconciliations and punishments, and in some instances it preceded secular executions — but it wasn’t automatically a death sentence.

When did the Inquisition begin?

The Medieval (Papal) Inquisition consolidated in the 1230s, when popes and local authorities developed more systematic procedures to investigate heresy in Western Europe.

When did the Spanish Inquisition end?

The Spanish Inquisition was abolished in 1834. By that point, Enlightenment critique, secular reforms, and political upheaval had steadily weakened inquisitorial power.

What are the most famous Inquisition trials?

The best-known case is Galileo (condemned in 1633 by the Roman Inquisition). Other famous episodes include high-profile prosecutions of suspected crypto-Jews and controversies over censorship — though the “typical” case was usually local, bureaucratic, and far less cinematic than pop culture suggests.

Sources & References

- Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision (Yale University Press, 2014).

- Edward Peters, Inquisition (University of California Press, 1989).

- John Tedeschi, The Prosecution of Heresy (Center for Medieval & Early Renaissance Studies, 1991).

- Christopher Black, The Italian Inquisition (Yale University Press, 2009).

- Primary documents: Papal bull Ad extirpanda (1252 CE); inquisitorial manuals and regional archives.

- Reputable digital collections and museum sites hosting inquisition archives and confessions.

More Articles