Machu Picchu: Lost City — Untold Story

Machu Picchu rises above the Urubamba like a stone mirage — a royal retreat, sacred landscape, and engineering masterpiece built where cloud forest meets high Andes.

Introduction

Riding a knife-edge ridge and wrapped in cloud forest, Machu Picchu is among the world’s most evocative archaeological sites. Perched at about 2,430 meters (7,970 ft) in Peru’s Andes, the site blends dramatic terrain with astonishing stonework — terraces, fountains, canals, and temples fitted so tightly that even today the masonry looks almost seamless. Often nicknamed the “Lost City of the Incas”, Machu Picchu was never truly “lost” to local communities; what changed in the early 20th century was global attention. Modern research also points to a more specific identity: not a vast metropolis, but a carefully planned royal estate and ceremonial center linked to Inca imperial power in the 15th century.

Where Is Machu Picchu—and Why Here?

Machu Picchu sits on a narrow saddle between Machu Picchu (“old peak”) and Huayna Picchu (“young peak”), above a bend of the Urubamba River. The site's altitude and setting are not mere backdrop—they are central to Inca planning. Terraces stabilize steep slopes, expand arable land, and manage water; channels and fountains deliver spring water with remarkable efficiency and durability.

The location also creates stacked microclimates. Inca planners used elevation changes, sun exposure, and airflow to support varied crops across terraces — a practical advantage in an empire that depended on resilient agriculture. The terraces were not only “fields on a cliff”; they were a system for soil control, drainage, and temperature buffering in a wet mountain environment.

Side fact: The altitude (≈2,430 m / 7,970 ft) places Machu Picchu in the cloud-forest belt, where orchids, hummingbirds, and mist are part of the experience—and the conservation challenge.

Lesser-known fact: Some historians argue that early documents may have referred to the site by a different name (often connected to Huayna Picchu), suggesting that “Machu Picchu” might not have been the primary historical label in every record — a reminder that famous places can acquire famous names later.

Fast Facts: Machu Picchu at a Glance

- Location: Eastern slopes of the Peruvian Andes, above the Urubamba River, near Cusco.

- Elevation: Approx. 2,430 m — 7,970 ft above sea level.

- Built: c. 1420s — mid 15th century, during the Inca imperial expansion.

- Primary function: Likely a royal estate and sacred retreat linked to the Inca emperor Pachacuti.

- Culture: Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu).

- Heritage status: Peruvian Historic Sanctuary (1981) — UNESCO World Heritage Site (1983).

- Modern recognition: Named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in 2007.

- Typical visit time: About 2.5–3 hours on regulated circuits with timed entry tickets.

-

15th–century context:

Built in the same century that saw Joan of Arc, the rise of Mehmed II, the printing press, and voyages like Columbus’s 1492 crossing reshape other parts of the world.

- Population at its peak: Probably a few hundred people — elite residents, priests, artisans, and attendants — rather than a large city, which helps explain why the site could be abandoned and overgrown without wide notice.

The Inca Citadel: Plan, Symbols, and Stone

Archaeologists often divide Machu Picchu into agricultural and urban sectors separated by a broad plaza. Around two hundred structures—dwellings, storage, and ritual spaces—are knitted into the terrain by terraces and stairways. The site's ashlar masonry (carefully shaped blocks set without mortar) shows the Inca mastery of local granite and seismic-resistant design.

Machu Picchu History: The Sacred Landscape

Temples anchor the urban core: the Temple of the Sun (Torreón), Temple of the Three Windows, Principal Temple, and the enigmatic Intihuatana (“hitching post of the sun”). The Intihuatana's carved pillar aligns with solar events, suggesting calendrical or ceremonial functions. What is clear is the Incas' careful choreography of architecture, sightlines, and celestial cycles.

Roads, Gates, and Views

Machu Picchu connects to the imperial road network. Approaching via the Inti Punku (Sun Gate) on the Inca Trail frames a ceremonial vista: terraces spilling down toward the Urubamba, the city cradled between twin peaks. The topography itself—rivers, ravines, and sacred mountains (apus)—forms a ritual landscape as much as a defensive one.

Who Built Machu Picchu—and When?

Most scholars interpret Machu Picchu as a royal estate of the Inca emperor Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (r. c. 1438-1471), created in the mid-15th century at the empire's apogee. Its elite residence compounds, ritual precincts, and agricultural zones fit the pattern of a royal retreat tied to power, ceremony, and display.

High-precision AMS radiocarbon dating has refined the timeline. A 2021 study of human remains from Machu Picchu’s cemeteries suggests occupation began by at least the early 15th century (around the 1420s) and continued until roughly the early 16th century (around the 1530s). Rather than overturning the Pachacuti connection, these dates help sharpen when the estate became active and how long it functioned before the upheavals of the conquest era reshaped the region.

Debate snapshot: Earlier theories cast Machu Picchu as a fortress, a nunnery, or even the true last Inca capital. Modern consensus favors a royal-estate model with sacred, agricultural, and astronomical roles interwoven.

| Interpretation | What it emphasizes | What the evidence suggests |

|---|---|---|

| Royal estate (leading view) | Elite residence, ceremony, display of power | High-status architecture, ritual precincts, managed agriculture — consistent with estates linked to imperial rule. |

| Sacred/ceremonial center | Calendrical ritual, cosmology, pilgrimage | Temple complex, sightlines, carved stone features — likely intertwined with estate functions rather than separate. |

| Fortress/refuge (older theory) | Defense and last-stand resistance | The terrain is defensive, but the layout better fits planned residence and ritual use than a purely military site. |

Why Was Machu Picchu Abandoned?

The short answer is that no single document explains a formal “abandonment order.” Instead, historians piece together a probable scenario from archaeology, regional history, and the timing of imperial collapse.

- Imperial disruption: After the Spanish conquest, the Inca political system that supported royal estates fractured. Sites tied to elite patronage likely lost labor, supplies, and protection.

- Population shock: Disease and forced relocations destabilized communities across the Andes, reducing the workforce needed to maintain terraces, canals, and roads.

- Strategic shift: In a period of conflict, people may have consolidated into more defensible or better-connected settlements rather than maintaining a high, specialized retreat.

- Local continuity, changing use: Even if elite residence ended, the landscape was not erased — knowledge of the ruins persisted locally while the site gradually re-vegetated.

In other words, Machu Picchu was likely “abandoned” as an imperial place before it was abandoned as a known place — a subtle but important distinction behind the “Lost City” label.

Machu Picchu in the 15th–Century World

While stonemasons shaped terraces high above the Urubamba, other corners of the 15th–century world were undergoing their own upheavals. In Europe, conflicts like the Hundred Years’ War produced figures such as Joan of Arc, while Ottoman expansion under Mehmed II transformed the map of the eastern Mediterranean. Within a few decades, the printing press would begin to spread ideas at unprecedented speed, and explorers such as Christopher Columbus would open new transoceanic routes.

Seen against this wider backdrop, Machu Picchu becomes more than an isolated “Lost City of the Incas.” It was part of a sophisticated imperial system in the Andes at the very moment when global connections were tightening elsewhere. Later Renaissance figures like Leonardo da Vinci worked with paper, ink, and gears; Inca engineers worked with stone, water, and gravity. Both, in different ways, were pushing the limits of what their societies could imagine and build.

“Lost” and Found: From Local Knowledge to Global Fame

On July 24, 1911, Yale lecturer Hiram Bingham reached the ridge with help from local residents who knew the terrain and the ruins. Bingham’s photographs and writing soon amplified Machu Picchu far beyond the region — especially after major publicity in the early 1910s that helped transform the site into a global icon. Importantly, Bingham did not “discover” Machu Picchu in an absolute sense; people living in the area already knew of the ruins and used nearby land. What Bingham’s expedition changed was international visibility and the scale of subsequent research.

Bingham initially believed he had found the Inca “Lost City” of Vilcabamba, the last royal stronghold against the Spaniards. Subsequent research identified the true last refuge at Espíritu Pampa, confirming that Machu Picchu was something else entirely—an interpretation that underscores how archaeology evolves as new evidence accumulates.

A related chapter concerns the artifacts taken to Yale for study. After a long dispute, Peru and Yale reached an agreement in 2010 to return the collection, now exhibited in Cusco in partnership with UNSAAC.

Engineering Genius in a Fragile Place

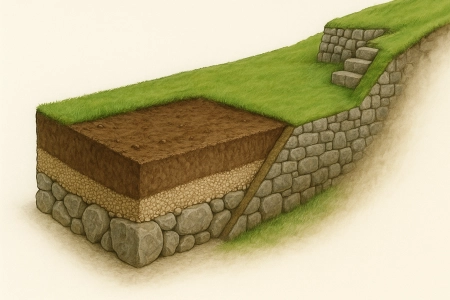

Machu Picchu endures not because it escaped time, but because Inca engineers anticipated it. Builders used trapezoidal doorways, inward-slanting walls, and interlocking blocks to dissipate seismic forces. Terraces acted as retaining walls and living drainage systems—stone, gravel, and soil layers that wick water downward and outward.

Excavations have revealed that much of Machu Picchu’s infrastructure lies out of sight. Beneath plazas and pathways, thick layers of stone and gravel act as an invisible sponge, drawing storm water away from buildings and into the slopes. Hydrologists have noted that the main spring was captured in a carefully lined intake box and routed along a gently sloping canal to a cascade of fountains, with surface runoff directed elsewhere so drinking water stayed clean. It is this hidden engineering — as much as the postcard view — that allowed the royal estate to function on such a precarious ridge.

Equally impressive, a spring-fed canal and series of fountains met daily needs while shedding excess flow during cloudbursts. These choices reveal an intimate dialogue with one of the planet's most challenging settings and help explain the citadel's longevity.

UNESCO Status, Stewardship, and Sustainable Visits

Designated a World Heritage Site in 1983, Machu Picchu is recognized for both cultural and natural values—rare among listings. The inscription covers the citadel and the surrounding sanctuary with remarkable biodiversity. With renown come risks: visitor pressure, landslides, and ecosystem stress. Timed entries, route planning, and reinvestment of tourism revenue aim to balance access with preservation.

Before its World Heritage inscription, Peru had already declared a broad zone around the citadel a Historic Sanctuary in 1981, recognising not only the ruins but also more than 300 square kilometres of steep valleys and cloud forest. The sanctuary protects a remarkable variety of species — from orchids and hummingbirds to spectacled bears and Andean condors — alongside the stonework. In 2007, a global public vote named Machu Picchu one of the New Seven Wonders of the World, reinforcing its status as both a national symbol and an international icon.

Modern Visitation — Circuits, Time Limits, Ticket Caps

- Timed entry tickets: Visitors enter in fixed time slots and usually follow one of several marked circuits through the site. Re–entry is not normally allowed once you exit the citadel.

- Stay duration: Standard tickets generally allow around 2.5–3 hours inside Machu Picchu, enough to complete a circuit at a steady but respectful pace.

- Daily caps: Authorities limit total entries per day — typically around 4,500 visitors, with capacity rising to about 5,600 during high season — to reduce crowding and wear on paths and terraces.

- Seasonal nuance: Peak months (roughly June to August) bring the heaviest crowds, while shoulder seasons such as April–May and September–November often balance clearer weather with slightly lighter traffic.

- Linked experiences: Separate tickets — booked well in advance — are required for popular add–ons like Huayna Picchu or Machu Picchu Mountain, and for multi–day treks on the classic Inca Trail.

Conclusion: A City Between Earth and Sky

Machu Picchu compresses an empire's ambition into stone—an Inca citadel that fuses engineering with sacred landscape. Royal estate, ceremonial center, and observatory: these roles overlap in a place where terraces become architecture and mountains become monuments. From Pachacuti's court to Bingham's photographs and today's carefully managed visitation, the “untold story” is less a single revelation than a century of evolving insight—an invitation to keep learning while treading lightly on a ridge between the Andes and the Amazon.

Machu Picchu — Frequently Asked Questions

When was Machu Picchu built?

Traditional readings of Spanish chronicles place Machu Picchu’s construction after 1440, during the reign of Pachacuti. Recent radiocarbon dating of human remains suggests the citadel may have been in use from around the 1420s to about 1530, meaning it was already active by the time the Inca Empire reached its greatest extent.

Why is it called the “Lost City of the Incas”?

The nickname comes from early 20th–century explorers and writers who portrayed Machu Picchu as completely forgotten until the 1911 expedition led by Hiram Bingham. In reality, local families and farmers in the region always knew the ruins were there. Archaeology has since shown that Machu Picchu was not the final Inca capital, but a royal estate and sacred site within a larger network of Andean centres.

Is Machu Picchu still structurally stable?

Yes — but it needs careful management. The Inca builders used inward–sloping walls, interlocking stone blocks, and deep drainage layers to cope with earthquakes and heavy rain. Modern challenges come more from erosion and visitor pressure than from design flaws. Conservation work focuses on stabilising paths and terraces so the original engineering continues to do its job.

What is the best time of year to visit?

The dry season (roughly May to October) offers more predictable weather and clear views, but also brings the largest crowds. Shoulder months such as April, May, September, and early November often balance good conditions with slightly fewer visitors. The rainy season can be atmospheric — with lush greenery and mists — but requires waterproof gear and more flexible expectations.

How does Machu Picchu compare to other 15th–century sites?

Machu Picchu is exceptional for the way it fuses urban planning with a high–mountain landscape. In the same century, European societies were witnessing turning points such as the career of Joan of Arc, the spread of the printing press, and voyages like Columbus’s 1492 crossing. Together, these stories show how different regions of the 15th–century world were changing at the same time, but along very different paths.

Sources & References

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu (official listing and site overview).

- Reporting on research by Brian S. Bauer and Donato Amado Gonzales discussing early-name evidence and the site’s historical labeling.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, entries on Machu Picchu and Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui.

- Yale News (2021), reporting on AMS radiocarbon dating that refines Machu Picchu’s occupation chronology.

- National Geographic (1913 special issue; later features) on Hiram Bingham's expeditions and photography.

- PBS NOVA interviews and Ken Wright, civil-engineering analyses of terraces, canals, and fountains.

- Studies identifying Espíritu Pampa as the final Inca refuge in Vilcabamba.

More Articles